Reposting this from Brooks Simpson's Crossroads blog where it appeared earlier today. Crossroads

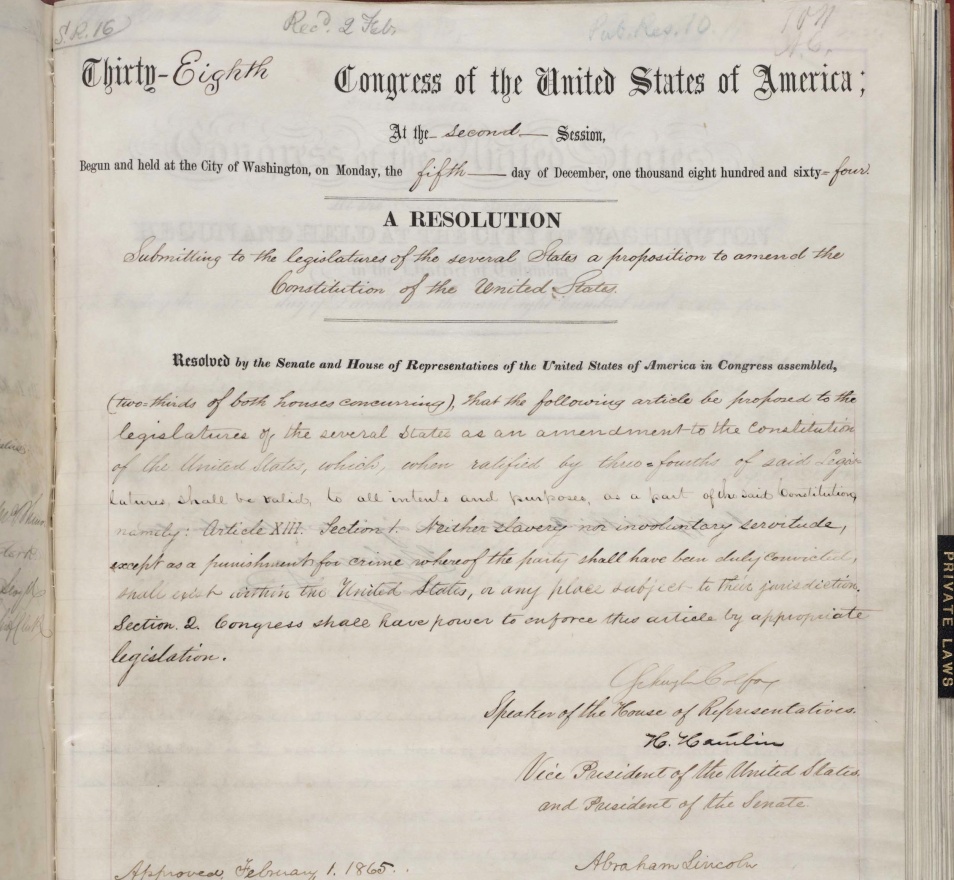

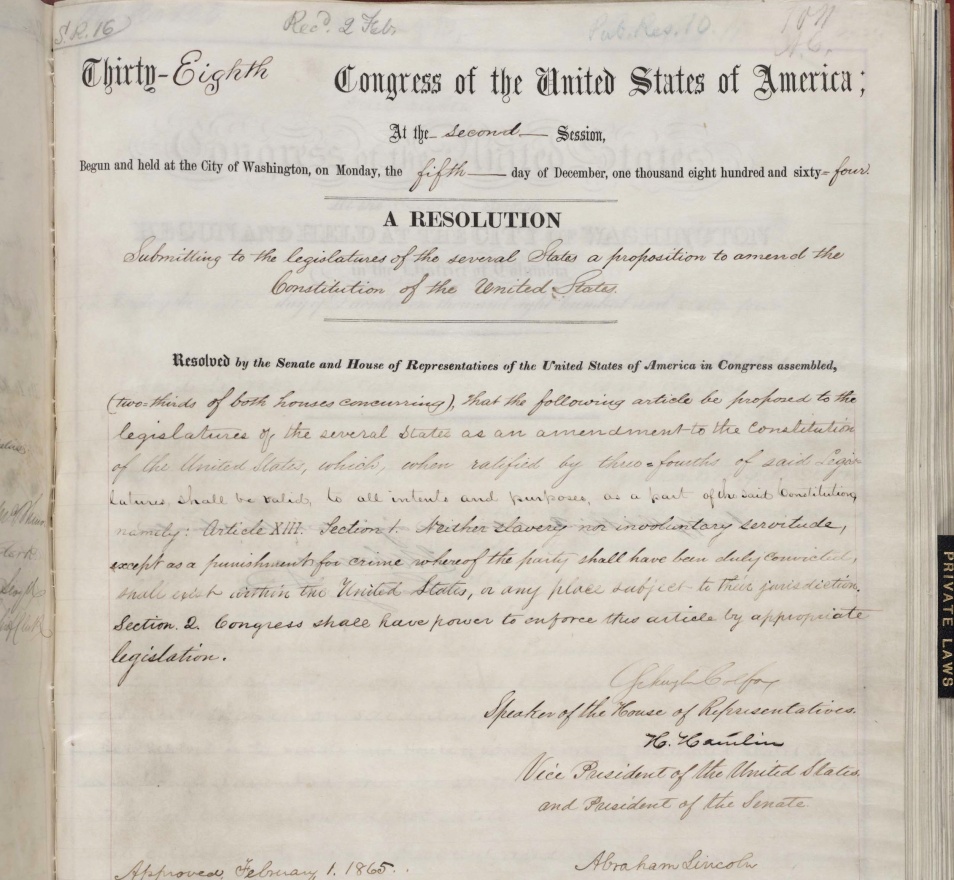

On December 6, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment became part of the United States Constitution.

Note that when the amendment went out to the state legislatures for ratification, Abraham Lincoln affixed his signature … an unnecessary part of the process. Just ask Andrew Johnson.

That’s how the New York Herald informed its readers of this event on December 7. Note that it was Georgia’s ratification that made the amendment part of the Constitution.

Free at last, indeed. What freedom would mean was still left to be defined.

One should note, however, the oft-overlooked exception:

—-

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

—-

Some people like to think this still means that slavery survives in some form. Apparently the phrase “involuntary servitude” escapes their notice. After all, a work crew of prisoners is engaged in “involuntary servitude,” and the amendment did not prevent the evolution of chain gangs.

Section Two would become familiar wording in the drafting of constitutional amendments during Reconstruction. Usually the story of the amendment ends with its ratification (and indeed the drama of the story ends with the congressional passage of the amendment). But southern legislatures knew better: several attempted to restrict the meaning of the second section because they were worried about how Congress might attempt not only to define but also to protect freedom. For those of you who think it would have been a good idea to let white southerners manage their own reconstruction, these reservations suggest that if left to themselves white southerners would have restricted black freedom to the bare minimum, as the Black Codes would suggest. So much for the fable of white and black southerners living together in blissful harmony.

For more, read Kevin Levin’s essay.

On December 6, 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment became part of the United States Constitution.

Note that when the amendment went out to the state legislatures for ratification, Abraham Lincoln affixed his signature … an unnecessary part of the process. Just ask Andrew Johnson.

That’s how the New York Herald informed its readers of this event on December 7. Note that it was Georgia’s ratification that made the amendment part of the Constitution.

Free at last, indeed. What freedom would mean was still left to be defined.

One should note, however, the oft-overlooked exception:

—-

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

—-

Some people like to think this still means that slavery survives in some form. Apparently the phrase “involuntary servitude” escapes their notice. After all, a work crew of prisoners is engaged in “involuntary servitude,” and the amendment did not prevent the evolution of chain gangs.

Section Two would become familiar wording in the drafting of constitutional amendments during Reconstruction. Usually the story of the amendment ends with its ratification (and indeed the drama of the story ends with the congressional passage of the amendment). But southern legislatures knew better: several attempted to restrict the meaning of the second section because they were worried about how Congress might attempt not only to define but also to protect freedom. For those of you who think it would have been a good idea to let white southerners manage their own reconstruction, these reservations suggest that if left to themselves white southerners would have restricted black freedom to the bare minimum, as the Black Codes would suggest. So much for the fable of white and black southerners living together in blissful harmony.

For more, read Kevin Levin’s essay.

No comments:

Post a Comment